| 3) II) Ordering geogr. space - G) commemorative policies | ||

|

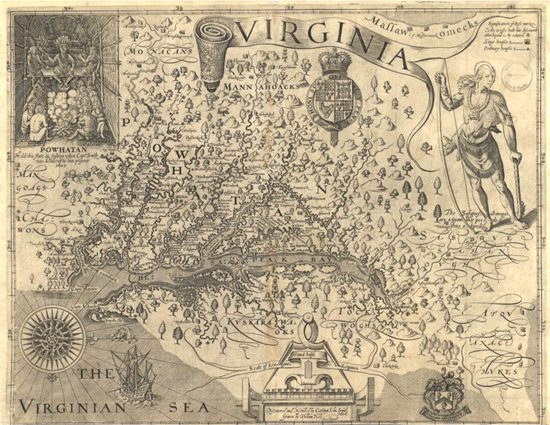

In Virginia, the land of Pocahontas, there initially was a good rapport between the English colonists and the local Indians. This is reflected in the early maps of the region drawn by John Smith (1612): apart from two English names all the names are clearly Indian (see map above). Later on, without any conscious effort to

exchange names of Indian derivation for those given by colonists,

the namescape of Virginia changed completely (see map below).

When we look at a current map introduced by the National Geographic,

it is English language names that stand out; the only name category

that has preserved its Indian character is that of the river names:

e.g. Chesaspeake, and Rappahannock. The only native place name

still rendered seems to be Tappahannock. So, even if this was

not the result of names planning it is a complete change of the

namescape.

It is usual to name objects discovered after the discoverer or after any other name he or she would have bestowed on the discovered object, such as the name of a patron or other worthy person or institution. Even today this practice continues in some areas. But these original names are not always kept. The name Spitsbergen was bestowed on the present Svalbard archipelago by the Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz in 1596, on his way to Novaya Zemlya,when looking for a northern route towards East Asia. In 1925 when the archipelago had been allocated to Norway, the latter opted for the name Svalbard. In a 12th century Icelandic text, this name (meaning cold rim or cold coast) was mentioned, probably however for a part of Greenland (see Politikens Nudansk Ordbog, 1992, under Svalbard). Most languages follow this Norwegian practice and use Svalbard when naming the archipelago and Spitsbergen when referring to its largest island. In the Dutch, German and Russian languages the original meaning is kept; here 'Spitsbergen' refers both to the archipelago and to its largest island. Svalbard is an example of a largely uninhabited area where, since it has been allocated to Norway, Norwegian officials have bestowed names of worthy countrymen and -women who in their opinion should be honored by naming a mountain, bay or island after them. An occasional Swede or Dane is also included in this toponymic pantheon. By this naming behavior the original names for objects in the Spitsbergen archipelago, given by the English and Dutch in the 16th and 17th century, have been swamped completely by this new influx of names, and the character of the namescape thus changed.

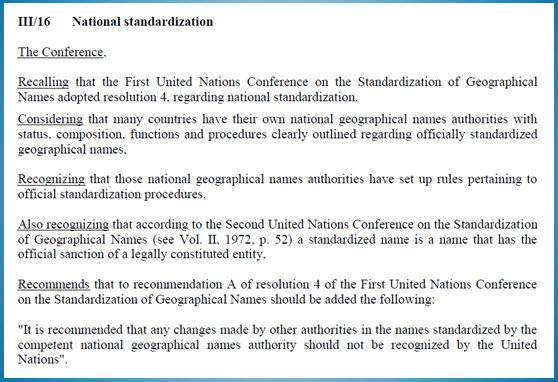

What is wholly reprehensible is the obliteration of existing place names and their replacement by placenames that suit those in charge. It is the toponymical counterpart of ethnic cleansing, and it happened under nationalist ideologies in both Europe and elsewhere. The United Nations have taken a strong stand against this particular aspect of names planning, in resolution III-16 and VI-9 (see UNGEGN webpage "Resolution on the Standardiazation of Geographical Names", click here for pdf, resp. pp. 32 and 34 and/or see images below).

|

||

|

Home | Self study : Toponymical Planning | Contents | Intro | 1.What is toponymical planning? | 2.I-Name changed due? (a/b/c) | 3.II- Ordering geographical space (d/e/f/g) | 4.III-Changing orthography (h/i) | 5.IV- Technical assistence |